Certain strands of music-cognition theory suggest that listeners entrain to one metric stratum at a time. We can hear a second stratum in terms of a first, or we can quickly flip between two perceptual orientations, or we can hear two strata as a single compound structure (London 2012). The first of these is a basic figure-ground relation, the second an example of multistability (Ihde 2012), the third a kind of perceptual gestalt (Pressing, Summers, and Magill 1996). In all of these interpretations, metric entrainment is assumed to be a singular process.

In the discourse of many African and Afrodiasporic practitioners, however, there are situations in which multiple metric strata co-function both phenomenally (materially present in the musical sounds) and perceptually (how practitioners learn to organize those sounds). Most important, since these musics (a) are highly improvisatory, and (b) almost always co-occur with dance, it is an important part of becoming an expert practitioner to learn to hear multiply, to learn to hold two or more metric interpretations at once. David Peñalosa (2009), for one, makes this clear: even though he insists that one beat level is always primary, he reinforces that fluent attention to what he calls secondary levels is a fundamental part of expert listening.

Two recent studies offer encouraging support for this notion. Ève Poudrier and Bruno Repp (2012) conducted an experiment to determine whether what they call "polymetric perception"—"the simultaneous perception and tracking of two independent beats" (371)—is possible, and while their findings are not fully conclusive (largely because of their experiment participants, all musicians trained in the Western "classical" tradition), they do open onto fruitful avenues for further exploration. More recently, Gérard Guillot (2020) has been developing an experimental framework for testing whether it is possible to entrain polymetrically, building on dynamic attending (Jones and Boltz 1989) and multiple oscillator synchronization models (Large and Kolen 1994). My own teaching and research hinge on the idea that embodied participation has a constitutive effect on perception, and that perception is itself something that occurs not only in the mind, but through the body and in conjunction with one's environment (see Gallagher 2016).

The musics toward which the following lesson leads are part of a class of African and Afrodiasporic practices I call timeline musics, due to the fact that they feature an asymmetrical "timeline" (see below) as one of a number of strata that come together to form a "multidimensional" nexus (Locke 2010). Because timeline musics are intricately, essentially entangled with dance, everyone involved is an active participant. The distinction between performer and observer is completely blurred: everyone is moving about, one may sing along, clap, shout, laugh, bang on a table top, play air drums. These are spaces of exuberant, improvisatory participation. As such, I feel it is valuable to create learning environments that are likewise actively engaging, as a practice of situated learning (Lave and Wenger 1990).

The scene that follows describes a version of a lesson I have given in music theory and "world music" classes and in workshops for all ages over the last fifteen years. I begin with an assumption that we can indeed hear multimetrically. With that assumption in mind, I take the reader through some introductory steps that can help a new participant begin to develop the embodied skills needed to do so, within the specific context of timeline music. Beginning with a basic beat sequence, I gradually introduce various additional performance layers, including additional beat sequences and other repeated rhythmic patterns that unfold alongside them, continuously recombining all layers so students experience them from multiple shifting embodied perspectives. While this lesson focuses on singing, clapping, and stepping, these are far from the only ways of producing sound and movement, and I encourage the reader to consider other modes of production that work for differently abled students.

Stepping and Clapping

Scene: A first-year music theory classroom at a US university school of music. 23 students; a loose balance between orchestral performers and pianists, opera singers, jazz musicians, music education majors. Little experience with non-Western music traditions, but quite a lot of experience listening to contemporary popular music in one form or another. The basics of meter and rhythm, including notation conventions, have been covered.

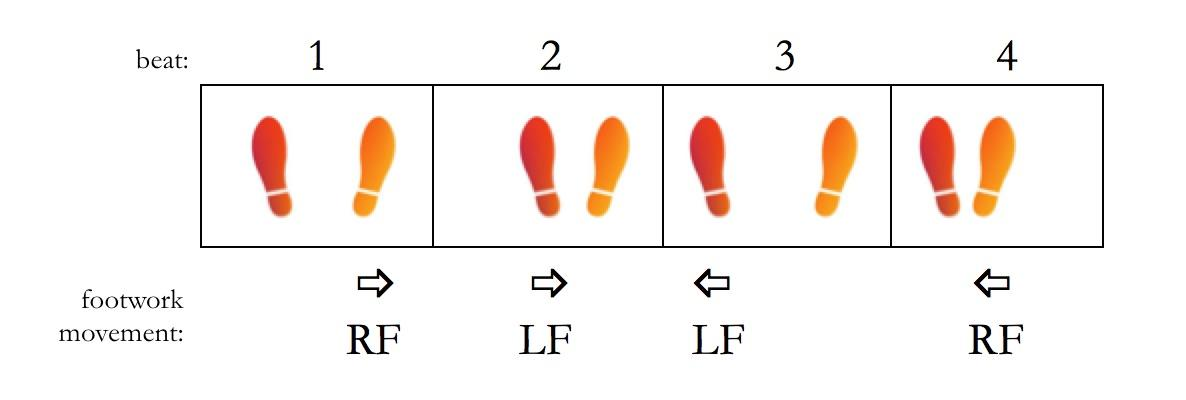

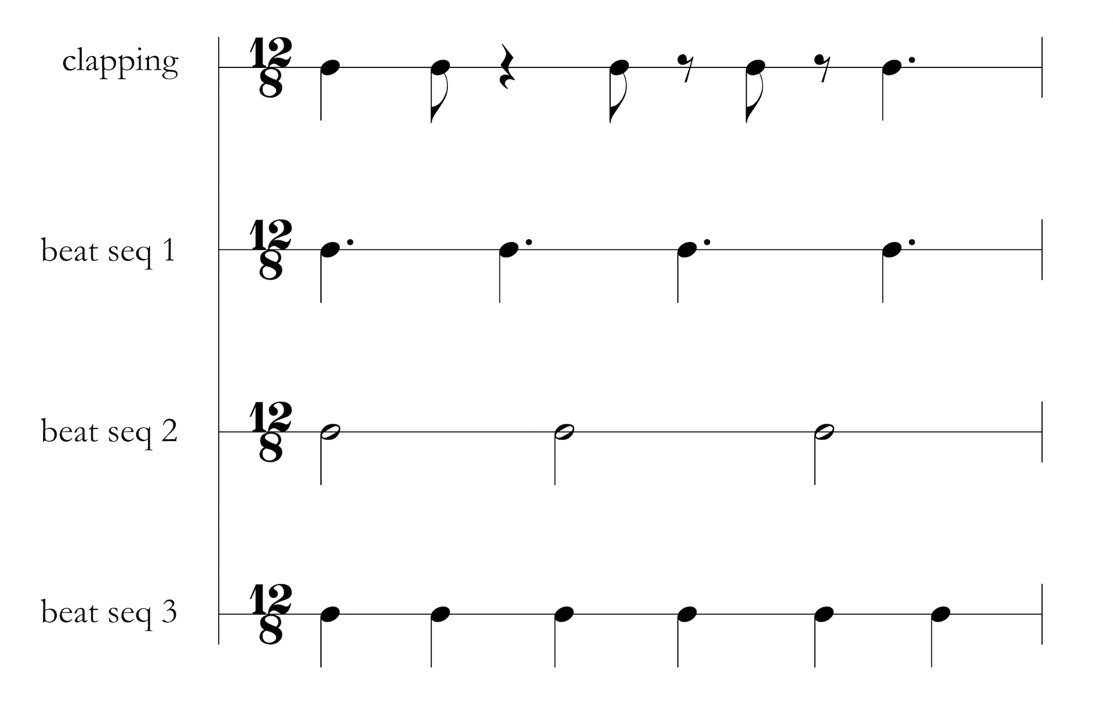

We stand and form a circle around the periphery of the classroom, facing center. We warm up by stepping together in the pattern right foot (RF) out—left foot (LF) in—LF out—RF in (Figure 1). I encourage everyone to let their arms swing freely, to smile, and to breathe deeply.

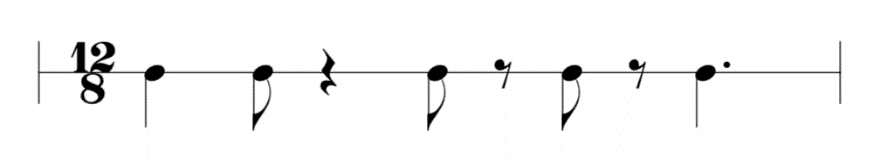

Once everyone is feeling the stepping sequence comfortably (maybe a minute or two), we pause and I ask them to listen a few times to the following sequence (Figure 2) and then join in clapping. (Please note: all of the figures that follow are for the instructor's—and reader's—benefit: all of the activities in this lesson are taught aurally and internalized through repetition. A lesson on different ways of notating different rhythmic relations could potentially follow this one.)

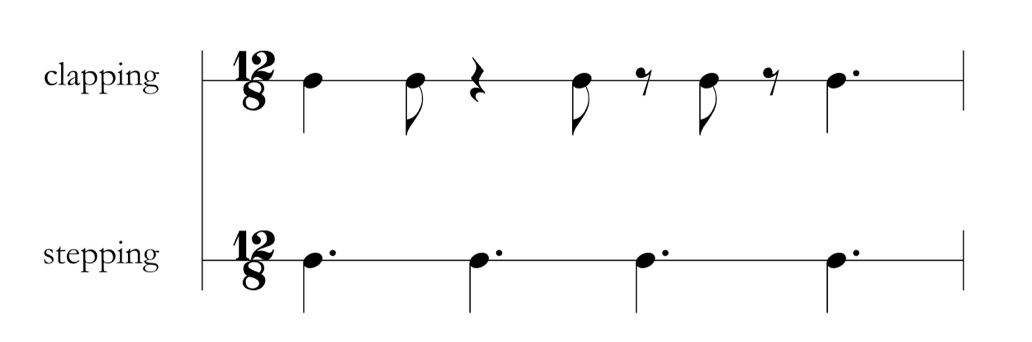

When we have reached an acceptable degree of ensemble precision (without worrying overly about exactness—I'm interested more in the shape of the gesture than in quantized perfection), we add the stepping routine we began with (Figure 3). We repeat this many times, and as the class is stepping and clapping, I draw their attention to a few interesting aspects of the relation between what their hands and feet are doing. For example, I point out how beats one (RF out) and four (RF in) converge with claps, while beats two (LF in) and three (LF out) and claps two, three, and four syncopate alongside one another (see Simpson-Litke and Stover 2019 for more on this usage). The feeling from this perspective is one of synchrony to asynchrony and back, as a kind of "wave" of directed energy.

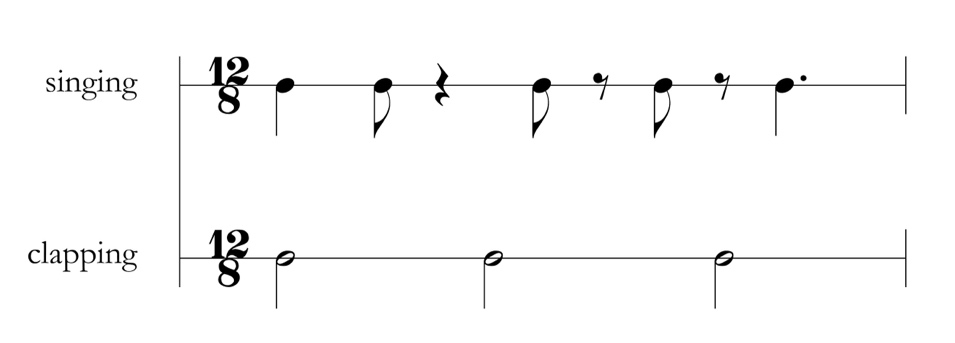

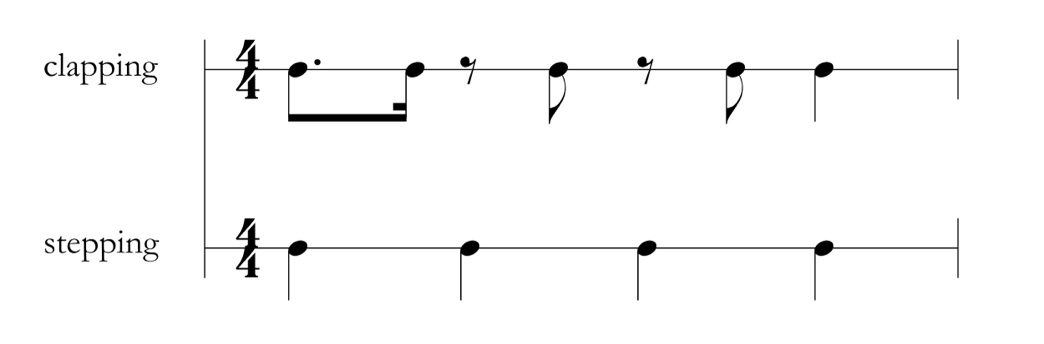

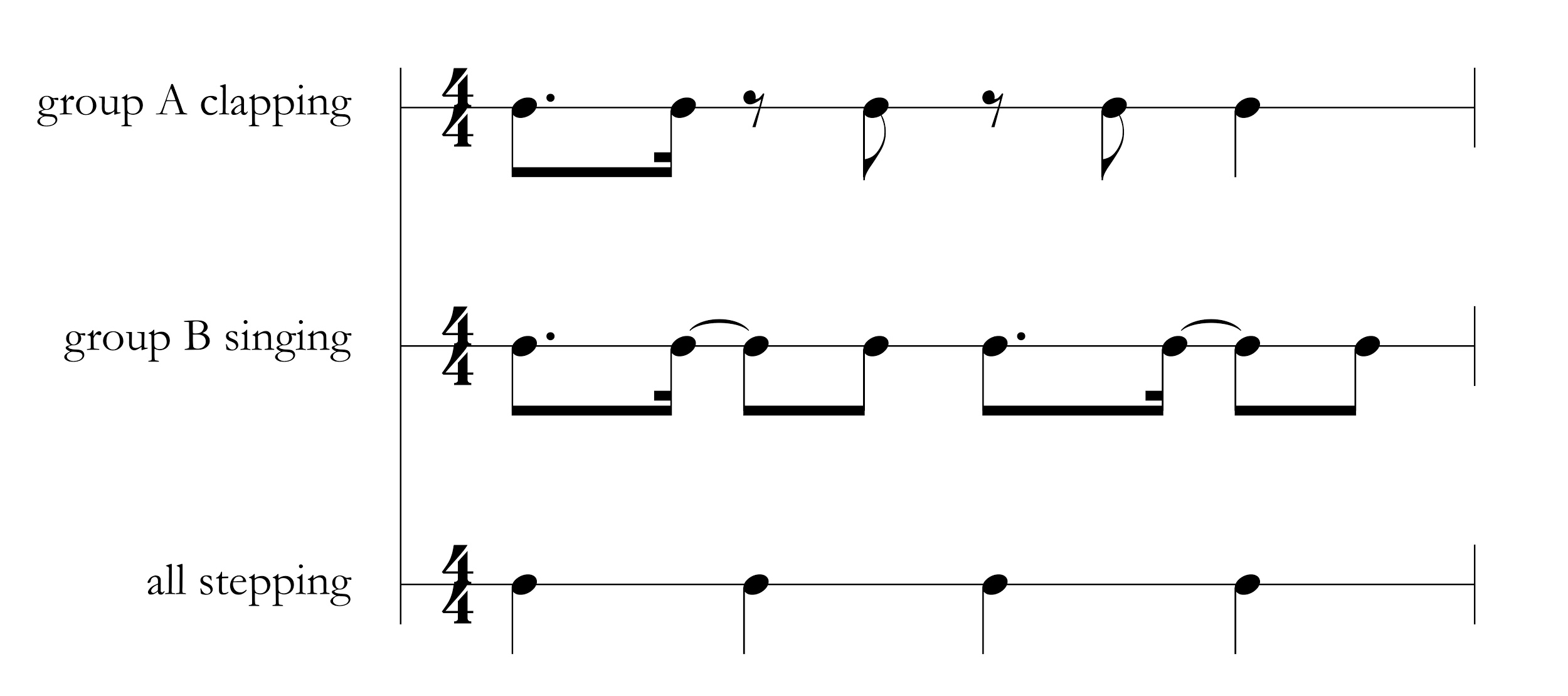

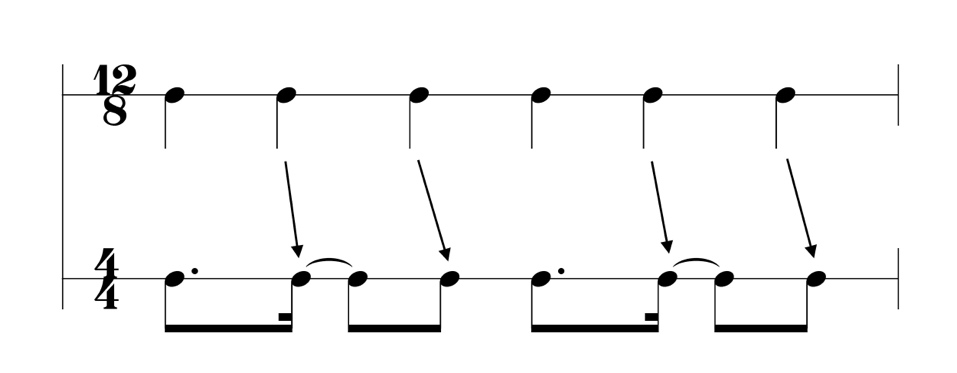

We pause again. Now we're going to come at the same context but framed (and performed) somewhat differently. I ask the class now to sing the clapping pattern, and to clap the beat sequence they were previous stepping. This is usually comparatively easy, having been clapping and stepping this pair of patterns for some time. I then ask them to stop clapping but keep singing, at which point I clap the following sequence (Figure 4, bottom staff), inviting them to join in once they've heard it a few times.

After we have achieved a degree of competence with this combination, it's time to pause for a brief analytic interlude to assess what we've done so far, and for some terminology. The five-onset asymmetrical sequence that we clapped and then sang is a version of son clave, named for a constellation of musical practices stemming from Cuba known as son. It is an example of a timeline, a consistently repeating rhythmic gesture that plays at least two important roles in its native contexts: as an orientation tool (helping participants find their place in sometimes quite complex multidimensional spaces), and as a legislative force (guiding improvisational possibilities within those spaces). Specifically, it is the version of son clave that scans along a twelve-pulse cycle, as represented by the 12/8 time signature in the notation so far (with eighth notes representing pulses). This particular timeline has special significance: A.M. Jones (1959) refers to it as the "African 'signature tune'"; Bertram Lehmann (2002) calls it the "syntactic background" and demonstrates how it underlies many other timeline sequences.

The two beat sequences we stepped or clapped outline four-count and three-count metric frameworks respectively. We affirm this by now clapping son clave and speaking the beat sequences: "one-two-three-four"; "one-two-three," each repeated several times. We keep clapping, and I speak an additional, six-count, beat sequence, asking them again to join me once they've heard it a few times (Figure 5, fourth staff).

We're ready to up the degree of difficulty. We divide into three groups. Everyone softly sings the son clave sequence. Group A claps the four-count metric sequence. Once that is well established, group B taps the six-count sequence on a surface: a chair back or table top (this to clearly distinguish aurally from the ongoing four-count sequence). Group C's task, for the moment, is simply to listen, to notice the relation between the two metric strata. We trade roles a few times, so everyone can perform each part as well as listen to the ensemble nexus.

The relation between four-count and six-count metric strata can indeed be heard as a composite figure, as a repeating 3:2 hemiola sequence. David Locke (1982) refers to this as the "cross-beat relation" and identifies it as fundamental to, for example, many Ghanaian drum-dance practices. But importantly, I ask the students to resist simply hearing it as a single compound phenomenon. In some important way, these are discrete metric strata, and part of the purpose of our task is to conceive of them as such, and to feel both strata as independent (but interconnected) elements of what Meki Nzewi (1997) calls the ensemble thematic cycle.

Perhaps it is easiest to accomplish this shift of perspective by introducing our third metric stratum. Groups A and B continue singing son clave and clapping/tapping the four- and six-count strata respectively (although note that we trade roles frequently, so everyone is singing and clapping every part at some point). Now group C joins by tapping (on a surface distinct from that of group B) the three-count stratum. Three metric strata are now co-occurring. This complexifies the multidimensional texture significantly. It also illuminates what I call conduit spaces between strata: shared features that help relate strata to each other in different ways. To wit:

- The four-count and six-count strata share an onset at the cycle halfway point (beat three and beat four respectively);

- The six-count stratum nests the three-count stratum;

- The son clave timeline syncopates differently alongside the three metric strata, bringing out different features of each by variably reinforcing or contradicting them.

We're moving between strata now, noting their similarities and discrepancies: how they interrelate and how they operate independently to create the ensemble texture.

Stretching the Cycle

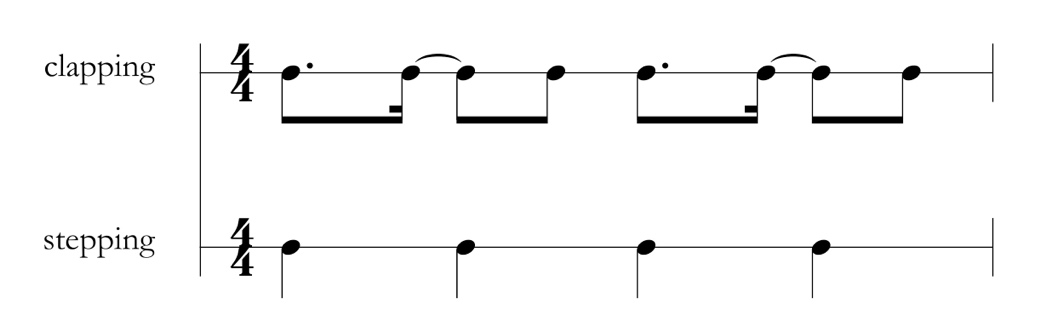

It's time for a quick break from stepping and clapping. We might take a moment and refresh some terminology, or talk about concepts of meter and rhythm we've been studying prior to this lesson/workshop. Then back to business. We begin again by stepping, RF out—LF in—LF out—RF in. I then clap the sequence shown in Figure 6 (top staff), asking them to listen very carefully before joining in. This always takes some time to cohere, since we've been working with a morphologically similar yet distinct sequence up to this point. Once we have this together and everyone is comfortable, I tell them this pattern is also called son clave! But as they can hear, it is stretched somewhat from what they've been experiencing so far.

While we all continue stepping, I clap a new pattern (Figure 7, top staff), again inviting everyone to join along once they've heard it a few times.

This pattern is called tresillo, a term that also derives from Cuban and Cuban-diasporic practice, but which has worked its way into many local discourses. We divide into two groups, all stepping the four-beat sequence. Group A claps tresillo. Group B sings son clave, in the new stretched version we've been working on (Figure 8). We note a new conduit space between the son clave timeline and tresillo, in that the first three onsets of each coincide, while the remainder syncopate alongside one another. We practice this for some time, trading parts, getting comfortable with hearing how they all interrelate.

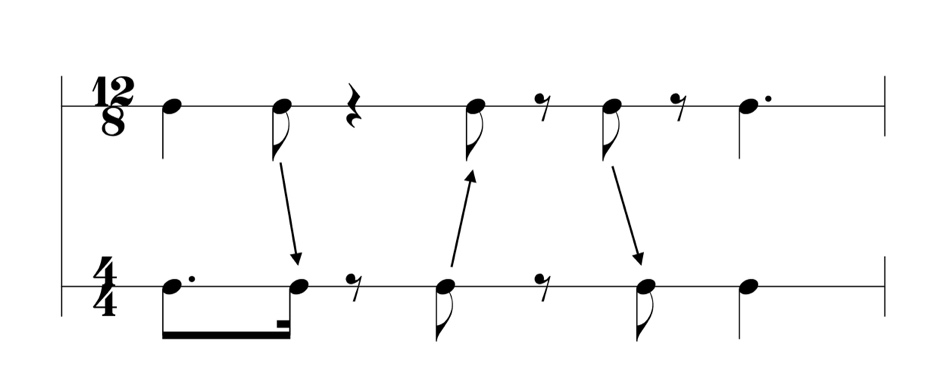

As noted, our new version of son clave stretches the previous one: it is relatively easy to hear the morphological similarity between the two (Figure 9, shown by arrows). While continuing to step our four-beat sequence, we practice moving between the two, a few iterations of each at a time.

What is important here, and a little more difficult to comprehend at first, is that tresillo similarly stretches the six-count metric stratum from our initial foray (Figure 10, shown by arrows). A better way to put this is that, in both cases, each version is a stretched form of the other: there is no priority between the two. In the case of the six-count metric / tresillo relation, the cycle beginning and halfway point share equivalent onsets, resulting in a different kind of directional impetus.

Tresillo is probably not a metric stratum. If it is, it is an example of non-isochronous meter: the 3+3+2 additive meter described by early Africanists like Rose Brandel (1962) and A.M. Jones (1959). I believe, however, that this overdetermines meter, by assuming meter is the only kind of periodic phenomenon to which one might entrain in a multidimensional musical context like timeline music. Instead, tresillo can be thought of as a periodic rhythm, which can also function as the recurring cyclic ground to which one attends and along which one comes to understand other events as syncopating. To think of the six-count metric stratum and tresillo as stretched versions of one another means, then, to be conceiving of meter and non-meter as a fluid spectrum. Meter is a "mode of attending" (Gjerdingen 1989), but not the only one.

Multi-Multi-Meter

The last step of our introductory project is the most abstract and challenging, but amplifies what is at stake in feeling and hearing multiple meters. We divide this time into four groups. We all resume stepping, RF out—LF in—LF out—RF in. Group A sings the original twelve-pulse version of son clave. Group B claps the six-count metric stratum. (It's important, I think, to be redistributing tasks in various ways so that everyone experiences different combinations in a directly embodied way, and I frequently reassign different parts to different participants in different combinations, and to redistribute the groups themselves.) The two groups repeat this configuration several times. They then stop, everyone still stepping, and group C sings the sixteen-pulse version of son clave while group D claps tresillo. We switch back and forth between the two, hearing and feeling the shift from twelve-pulse to sixteen-pulse cycles, all articulating along a consistent four-count stepping pattern.

We then try different combinations: one group clapping the twelve-pulse and sixteen-pulse versions of son clave in alternation; two groups clapping each version simultaneously, each trying to "hold their ground"; perhaps even performing a gradual phase shift from one to the other (advanced!). Same with the six-count cycle and tresillo. We listen to a few examples: samba de chula from Brazil, rumba columbia from Cuba, Igbin drumming from Nigeria, Zaouli from Cote d'Ivoire. I might interject with a few stories about my own experience learning to navigate this doubly multi-metric fabric (multiple traversals of a single pulse cycle; multiple co-extensive pulse cycles).

All of this is a gateway to thinking about improvisation and even the very idea of groove as a kind of elastic phenomenon. To this end I direct students (and the reader) to the illuminating work that has been done on expressive timing and groove in Afrodiasporic musics: the liminal triplet cubano (Bøhler 2013), "beat bins" (Danielsen 2010), suingue baiano (Gerischer 2006), "fix" (a portmanteau of four and six; Spiro 2006); "beat span" (Stover 2009). As all of these theories suggest, multiplicity and liminality are fundamental to these Afrodiasporic traditions, and coming to understand them—coming to hear them (Chernoff 1997)—as such is both a crucial and extraordinarily enjoyable entry point. And participatory, embodied engagement is a valuable—indeed an essential—entry point for coming to understand, feel, and internalize both meter and microtiming as multi-stable phenomena.

Bibliography

- Bøhler, Kjetil Klette. 2013. "Grooves, Pleasure and Politics in Cuban Salsa." PhD Dissertation, University of Oslo.

- Brandel, Rose. 1961. The Music of Central Africa: An Ethnomusicological Study: Former French Equatorial Africa, The Former Belgian Congo, Ruanda-Urundi, Uganda, Tanganyika. M. Nijhoff. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-015-0997-8

- Chernoff, John Miller. 1997. "'Hearing' in West African Idioms." The World of Music 39: 19–26. https://www.jstor.org/stable/41699143

- Danielsen, Anne. 2010. "Here, There and Everywhere: Three Accounts of Pulse in D'Angelo's 'Left and Right'." In Musical Rhythm in the Age of Digital Reproduction, ed. Anne Danielsen. Ashgate, 19–36. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315596983-2

- Gallagher, Shaun. 2016. Enactivist Interventions: Rethinking the Mind. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780198794325.001.0001

- Gerischer, Christiane. 2006. "O Suingue Baiano: Rhythmic Feel and Microrhythmic Phenomena in Brazilian Percussion." Ethnomusicology 50(1): 91–119. https://www.jstor.org/stable/20174425

- Gjerdingen, Robert O. 1989. "Meter as a Mode of Attending: A Network Simulation of Attentional Rhythmicity in Music." Intégral 3: 67–91.

- Guillot, Gérald. 2020. "Experimental Design for Testing a Hypothesis about Polymetric Structures in Afro-Brazilian Music." Unpublished manuscript.

- Ihde, Don. [1986] 2012. Experimental Phenomenology: An Introduction. Second Edition. State University of New York Press.

- Jones, A.M. 1959. Studies in African Music. Oxford University Press.

- Jones, Mari Reiss and Marilyn Boltz. 1989. "Dynamic Attending and Responses to Time." Psychological Review 96(3): 459–491. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.96.3.459

- Large, Edward W. and John F. Kolen. 1994. "Resonance and the Perception of Musical Meter." Connection Science 6(2–3): 177–208. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540099408915723

- Lave, Jean and Etienne Wenger. 1990. Situated Learning: Legitimate Peripheral Participation. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511815355

- Lehmann, Bertram. 2002. The Syntax of "Clave"—Perception and Analysis of Meter in Cuban and African Music. MA Thesis, Tufts University.

- Locke, David. 1982. "Principles of Off-Beat Timing and Cross-Rhythm in Southern Ev̲e Dancing." Ethnomusicology 26(2): 217–46. https://doi.org/10.2307/851524

- Locke, David. 2010. "Yewevu in the Metric Matrix." Music Theory Online 16(4). https://doi.org/10.30535/mto.16.4.3

- London, Justin. [2004] 2012. Hearing in Time: Psychological Aspects of Musical Meter. Second Revised Edition. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199744374.001.0001

- Nzewi, Meki. 1997. African Music: Theoretical Content and Creative Continuum: The Culture-Exponent's Definitions. Institut für populärer Musik.

- Peñalosa, David. 2009. The Clave Matrix: Afro-Cuban Rhythm: Its Principles and African Origins. Bembe Books.

- Poudrier, Ève and Bruno H. Repp. 2012. "Can Musicians Track Two Different Beats Simultaneously?" Music Perception 30(4): 369–390. https://doi.org/10.1525/mp.2013.30.4.369

- Pressing, Jeff, Jeff Summers, and Jon Magill. 1996. "Cognitive Multiplicity in Polyrhythmic Pattern Performance." Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance 22(5): 1127–48. https://doi.org/10.1037/0096-1523.22.5.1127

- Simpson-Litke, Rebecca and Chris Stover. 2019. "Theorizing Fundamental Music/Dance Interactions in Salsa." Music Theory Spectrum 41/1: 74–103. https://doi.org/10.1093/mts/mty033

- Spiro, Michael. 2006. The Conga Drummer's Guidebook. Sher Music Co.

- Stover, Chris. 2009. A Theory of Flexible Rhythmic Spaces for Diasporic African Music. PhD Dissertation, University of Washington.