Instructors of music theory face four basic questions when they plan a course: which contents to cover and how to spread them over time; which pieces to bring into class to illustrate these topics; how to foment and evaluate proficiency; and how to engage the students in performance, which may include but is not limited to the development of aural skills. In other words, schedule, repertoire, homework and testing, and in-class music making. Dictated by institutional demands, the choice of textbook, and the instructor's own proclivities, the answers to these questions sometimes have more to do with a checklist of things students need to demonstrate, and less with the intention to serve their actual interests and purposes. When such a gap between the objectives of the class and the students' goals stretches too wide, music theory courses run the risk of becoming alienating and unappealing.

I've learned this the hard way. Here is the story: in the Spring of 2016, the University at Buffalo's Department of Music revamped its single-term, three-credit music theory course for non-music majors, MUS 116. The class's new syllabus was based on a straightforward but comprehensive textbook, Joseph N. Straus's Elements of Music (3rd ed., 2012), whose topics went from the basics of notation to principles of functional harmony, and sections were capped at 44 students—rather than the previous recital-hall-filling model—so that a graduate teaching assistant could handle a section's teaching and grading entirely on their own and thus connect better with students. Sight-singing and dictation exercises are largely unviable to assess in test situations in classes like MUS 116, so this new syllabus also relieved the students of the burden of aural skills homework and exams and instead routed their energy to the text's plentiful written assignments, which even included setting short poems to music. Ideally, this different approach would both entice and prepare MUS 116's alumni to tackle the rigorous music theory courses UB required of freshman music majors, if they wished to, or at least send them off to their own fields of study excited about music.

The high incidence of failing grades and critical student evaluations, however, revealed that the class's expectations had backfired. Anticipating a fun low-level class outside their major, students felt frustrated by the class's snowballing complexity, and the imposition of a homework regimen they perceived as abstruse and overtaxing. Many also felt steamrolled by the class's schedule, complaining that too little time had been dedicated to difficult concepts, e.g. identifying the roots and qualities of inverted triads, before moving on to new topics. The Department acknowledged these issues halfway through the term, reduced the homework load by about 30% after midterms, and then in subsequent iterations of the class gave teaching assistants greater latitude to how they approached the syllabus, but a serious overhaul of the course would not happen until early 2020. By then, the course's unpopularity—as well as certain changes made to the undergraduate curriculum—had caused demand for the class to drop dramatically.

The capital sin of MUS 116's 2016 syllabus was prizing academic rigor and specialist knowledge above the two main goals of the class's usual crowd: 1) obtaining a good, relatively trouble-free grade; and, 2) deepening their understanding of relatable repertoire. While it is true that the majority of enrollees signed up for the class out of necessity, i.e. to satisfy certain undergraduate general education requirements, they also tended to favor MUS 116 over other applicable courses because they hoped it would advance or at least complement the musical interests they already had. Many students had a history of instrumental or vocal performance, many dabbled in audio production, and others came into the course having already developed mature critical thinking about music. Passion was the most common denominator. Yet, most of these students had no intention of taking up a music major or minor, and the very few who did became discouraged by MUS 116, not energized. When students realized they had to exert excessive effort to meet the class's academic demands, and were unable to see how those demands applied to their varied musical interests, demotivation set in, lectures became dry and tempting to skip, and studying, a chore.

I first taught this revised version of MUS 116 in its inaugural semester, as a first-year PhD student, and then five more times before graduating. Although the textbook remained the same—as did most of the syllabus, on the surface—the students' reactions caused my approach toward homework to grow more flexible over time, and the repertoire discussed in class less anchored in the Classical canon. This latter point stemmed as much from a desire to be truer to my own weird tastes as it did from the understanding that a diverse array of musical works and composers would lower the possibility of marginalizing students because "the choice of repertory within the classroom and textbooks is one way a course structure communicates identity-based values" (Palfy and Gilson 2018, 84). Besides, who could resist not using something like Attack on Titan's theme song and its cascading descending thirds to show how intervals impact melodic contour, when students had responded so positively to it in the past?

After graduation, UB offered me a full-time job, and put me in charge of MUS 116's two remaining sections. With my new position and the faculty members responsible for the 2016 syllabus gone, I eventually obtained the blessing of the Department's chairperson and my senior music theory colleague to reformulate the course and come up with a fresh syllabus. With four years of experience teaching this specific course, I strongly felt that a less orthodox homework structure and—most importantly—a shift of the class's focus from a theory of Western music to a theory of global music making were necessary to revitalize MUS 116. This shift meant situating the usual concepts of first-semester music theory in a non-dogmatic, geographically-diverse repertoire, and then instigating a conversation that made sense of them in light of the works' cultural contexts. After all, if there is a growing consensus that "music theory can be taught [to music majors] with a focus on present-day music making without shying away from its pluralistic complexity," how much more should it be so in courses for non-majors, who often find the "serious disconnection between higher education music programs and real-world musical practice" intolerable (Davidson and Lupton 2016, 177, 188)?

My first step consisted of supplementing the course's standard be-able-to learning goals with four fuzzier objectives: explore the universalities and particularities across a diverse range of global music-making practices to inspire curiosity and connection; develop critical mechanisms to argue for the appeal of a piece of music, or the lack thereof, in order to go beyond the noncommittal "music is subjective" crutch; find inspiration to enrich current pursuits, like playing in a band; and compose an original song.

Unable to find a textbook entirely suited for the new course's agenda, I settled for an otherwise first-rate music fundamentals eBook with an online self-grading homework system,The Musician's Guide to Fundamentals by Clendinning, Marvin, and Phillips (3rd ed., 2018), and supplemented it with twenty-three self-penned case studies—roughly, one for every other class. Each case study began by pointing students to a readily accessible, high-quality but non-academic multimedia source dealing with a musical phenomenon from around the world, e.g. an article by Pitchfork on the omnipresent McDonald's jingle, a radio piece on the West African kora featured on PRI's The World, an Early Music Sources video explaining the use of "enharmonic" notes in late 16th-century Italy. After spending between 10-15 minutes of a lecture on a case study, students were encouraged to continue exploring the topic at home, and we moved on to doing the usual stuff of music theory classes. Also, to mitigate the intentional but potentially disorienting pinballing of themes, these case studies were shaped and arranged following the textbook's order of contents. This reinforcing relationship between the textbook and the case studies likewise contributed to a more forgiving pace in the schedule because it permitted us to dwell on each topic a little longer than we otherwise would have done, which proved especially helpful when it came to challenging materials like the circle of fifths or the intervals between scale degrees of major and minor scales.

The breadth of phenomena considered—from Japanese anime to Georgian polyphonic singing to Swedish metal and beyond—kept lectures fresh, and because many of the themes had been deliberately picked according to trends I had observed among my students, the likelihood of personal investment on the part of MUS 116's diverse group of students also grew. An in-class discussion about the applicability of topics of music theory in these contexts would take place, and the case study ended with an essay prompt that helped students develop critical thinking about music instead of requiring right-or-wrong answers. For instance, after observing how strongly video-game themes resonated with students, we began our examination of minor scales with a case study about the head-scratching appearance of a Hebrew folk melody, "Mayim Mayim," in Japanese video games, and the students ate it up. Occasionally, my goal with these case studies was the same as Colleen Renihan's in her experiment with the online tool Twine, that is, to give students "the opportunity to consider in closer detail that act of attributing representational or narrative qualities to [music]" (Renihan 2015), like when I asked them to come up with a story to depict a konnakol duet; some other times, I simply wanted them to probe their notions about music, and hopefully consider them from an unusual angle.

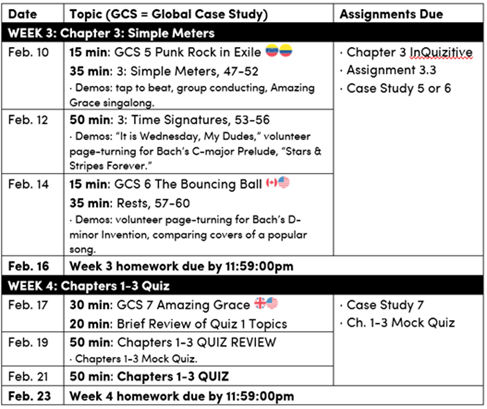

Here is a more detailed example: Figure 1 below consists of an excerpt of the class's schedule, detailing the themes, activities, assignments, and case studies dealt with during the third and fourth weeks of the semester. By this point, students were expected to identify and write notes using treble and bass clefs, and work with basic rhythms and rests in simple meters. Given their recently acquired musical literacy, case studies started to employ more involved excerpts of notated music to substantiate critical discussions. The case study of that week used a radio piece by Studio 360 on the history of "Amazing Grace" to jumpstart a conversation on the tandem evolution of the hymn's performance practice and social meaning. We had sung "Amazing Grace" together the week before by following a score projected on a screen; since most students already knew the tune from before—even foreign nationals and non-Christians—our singing exercise turned out to be a relaxed way of introducing the concept of score-directed music-making. After learning about the hymn's Anglican roots and inspecting the scores for two tunes associated with it, "Hephzibah" and "New Britain," the case study focused on the correlation between the song's transcendence as an American Civil Rights anthem and performers' growing preference for slower tempos and melodic ornamentations.

The discussion culminated with a viewing of Aretha Franklin's breathtaking 1972 performance of "Amazing Grace," and students were invited to produce a one-page-long reflective essay on the fluidity of musical style and performance practice, especially as it pertained to a specific artist or band they enjoyed. These essay prompts were purposefully tangential to motivate independent thinking; after participating in a discussion with curated topics and objectives, the student had to take a general principle raised in class and apply it to something of their own choosing. One student, for example, took this opportunity to argue that Maroon 5 had peaked with its debut album in 2002 because its stylistic shift from pop rock to electropop over the years had been more motivated by market pressures than artistic ones.

Figure 1: Schedule of weeks 3 and 4, including estimated time allotments for textbook contents and case studies covered in class, demo exercises, and assigned homework.

Although we examined twenty-three case studies in the semester, students only had to turn in thirteen essays, i.e. one a week, so they could pick their favorite topics. If they chose to write more than the required thirteen, their additional work would count toward extra credit, which was particularly useful to cover slip-ups such as underperforming on a quiz. Additionally, these essays provided a refreshing counterbalance to the more traditional, right-or-wrong assignments that students also had to complete, like labeling intervals or assigning Roman numerals to triads. Due dates kept students consistently engaged, but overdue essays were also accepted with a nominal grade penalty, and as a result, both the rate and the overall quality of submissions were great by the end of the semester.

Yet, despite their success, these types of qualitative assessments are rare in music theory curricula, let alone on issues surrounding global music phenomena. Many must oppose them on the basis of "lack of time, irrelevance of the course of study, [or] a narrow view of what learning [music theory] entails," but they ignore how reflective writing can turn students into "apprentices in the trade of interrelating music reading, hearing, and imagining rather than holding them accountable to the tasks of the textbook;" music theory becomes "intrinsically related" to music making, and the students, better able to find relevance in the class's materials (Davidson, Scripp and Fletcher 1995, 20-22).

I feared, however, that MUS 116's spread-out schedule, thematic unorthodoxy and accommodating homework system might have fallen flat if the students did not actually make music, so I planned for and facilitated at least one instance of collective music making per class. As Green and Hale (2011, 47) put it, when "activities at the heart of music are employed, motivation can be sparked and a learning orientation [rather than a grade orientation] takes over." These activities included singalongs with me at the piano or guitar, multiple-choice dictations with randomly selected students, dividing the class into groups and clapping rhythmic patterns, writing songs on the fly together, turning memes into music, etc. Then, to more completely emphasize the nexus between music theory and music making, I decided to scrap MUS 116's three-hour sit-down final exam, and replaced it with a songwriting project (although by "song" what I really meant was a pop-music-influenced composition, with or without vocals).

To accomplish this, I set aside six whole class periods late in the semester to run a kind of songwriting workshop, where we went over the final's guidelines in great detail. To meet the final's criteria, students had to know how to work with formulaic harmonic progressions, balance consonance and dissonance in the melody, and understand the normative alternation of verses, choruses and a bridge in pop music, so we dedicated these lectures to analyzing student-requested songs and workshopping their works-in-progress. In the interest of curtailing apprehension, a blank song template was made available, and three advanced music-major tutors stood at the ready for anyone who needed a bit of extra help. Likewise, students were given the option to work alone or in pairs, and except for the mandatory presence of properly built and labeled chords, there were no stylistic restrictions. Lyrics were optional, instrumentation was open, and students did not have to worry about performing their works; when the time came, I would be glad to play and/or sing them if they wanted me to—though several students who liked singing or were experienced with DAWs were glad to show off.

When the submissions started coming in, I was thrilled to see that the students had responded to the diverse repertoire studied in class with equally diverse offerings, ranging from chiptune and synthwave to piano ballads and even a viola duo. 1 In the end, the students' final projects required about as much time as if they had studied for and taken a conventional final exam, minus the stress: since their grades would come from PDF scores they had to submit—even for those who also uploaded recordings—the students could set their own working pace, and consult with me or any of the course's tutors at any point in the process. When we did come together to play and sing each other's works, everyone had already turned in their PDFs, and we were able to focus on making music without worrying about any other impact to their grades.

The decision to conclude MUS 116 with a songwriting unit did not come easily. I knew we would have to cut our discussions of functional harmony short, and that some students would resist the final project's unusual format or shrink from the task for fear of appearing vulnerable or inadequate. What I did not expect, though, is that most of the students who felt uncomfortable with writing and sharing a song would still end up getting an A in the class. Since unassigned exercises from the textbook could also be turned in for extra credit, these students rechanneled their efforts into completing enough extra-credit essays and assignments to make up for not doing the final. So, even though I felt they were missing out, I was glad to learn, ex post facto, that I had inadvertently designed the course in a way that enabled students like these to bypass the final project and redirect their energy into a more traditional mastery of music theory; a couple of students even went so far as completing an entire textbook worth of exercises!

If one gives any stock to the students' reactions to a course—as I certainly do—then I am both satisfied and optimistic about this reformulated MUS 116 and the ideological decisions behind it. Surely, there remain improvements to be made, specifically in tweaking the schedule, tightening the connection between the case studies and the contents from the textbook (this one or whichever else), reaching further beyond musics based on tonal harmony, and ensuring the essay prompts are absolutely clear and pertinent. These issues notwithstanding, the union of these four approaches—clement schedule, globally diverse repertoire, flexible homework, and abundant in-class music making—has already made for a much more meaningful experience for me as instructor, and has offered a viable solution to the course's previous prospects of extinction as well as a new paradigm for my non-music-theory-related syllabuses. A far cry from the opinion of a displeased 2016 student who called MUS 116 a "highly useless [class]," a flattering and hopefully honest student recently said that, "[this course] felt really personal and (…) the class as a whole felt like a team." As one who does not fetishize music, valuing it instead mostly for its potential for bringing people together and catalyzing a deeper sense of belonging, I could wish for no greater compliment.

Bibliography

- Davidson, Lyle, Larry Scripp and Alan Fletcher. "Enhancing sight-singing skills through reflective writing: A new approach to the undergraduate theory curriculum." Journal of Music Theory Pedagogy 9 (1995): 1-28. Accessed May 29, 2020. https://drive.google.com/file/d/1b40DNdV1v75DlpTkHIXOiHK6QAxMoNOk/view.

- Davidson, Robert and Mandy Lupton. "'It makes you think anything is possible': Representing diversity in music theory pedagogy." British Journal of Music Education 33, no. 2 (July 2016): 175-189. Accessed May 27, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0265051716000115

- Green, Susan K. and Connie L. Hale. "Fostering a lifelong love of music: Instruction and assessment practices that make a difference." Music Educators Journal 98, no.1 (September 2011): 45-50. Accessed May 29, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1177/0027432111412829

- Palfy, Cora S. and Eric Gilson. "The hidden curriculum in the music theory classroom." Journal of Music Theory Pedagogy 32 (2018). Accessed August 8, 2020. https://drive.google.com/file/d/1O8jHtZ_RUL31agfYxW4-8KzZ2KOJPeba/view.

- Renihan, Colleen. "Unraveling the narrative approach: Twine as music pedagogy." Engaging Students: Essays in Music Pedagogy 3 (2015). Accessed August 8, 2020. https://doi.org/10.18061/es.v3i0.7207

Notes

- All examples shared by permission of the authors.

Return to Text

Erratum

2/18/2022: Added Anabel Maler to list of peer reviewers.