In Fall 2015, students at Ithaca College walked out of class to protest, in part, systematic racism on campus. In response to the resulting discussions, students in the School of Music formed a group to advocate for the inclusion of music outside the Western canon in their performance and classroom spaces and flexibility within their curriculum to count in-depth study and performance of diverse musics as part of the core course work required for music majors. These desires for inclusion and agency colored the concurrent curricular redesign efforts in the School of Music, in which the faculty of the Music Theory, History, and Composition Department were reimagining the construction of the undergraduate theory and history core. This essay documents the multi-year process the Theory area faculty went through to arrive at their contributions to what we call the FlexCore (the common requirements across music degrees), specifically describing the challenges we addressed and our end result for the new Theory curriculum.

The Ithaca College School of Music Faculty started the process of curricular change before the events of Fall 2015, but input from alumni and current students surveys echoed the same call for more inclusion and flexibility in the degree programs. Working in dialogue with our Curricular Revision Team, we created the framework of the FlexCore based on curricular discussions across all departments to address these issues. As part of the process to arrive at this design, which cuts the number of required shared courses in order to allow upper-division electives in Theory, History, and Aural Skills, the Theory area spent two years proposing curricular models, discussing course content, and developing learning objectives and syllabi. As such, this modular approach to the Theory core reflects the collective pedagogical work of an entire school, but specifically the Theory area, and this essay contextualizes this work in current pedagogical thought around inclusion and agency in the college classroom.

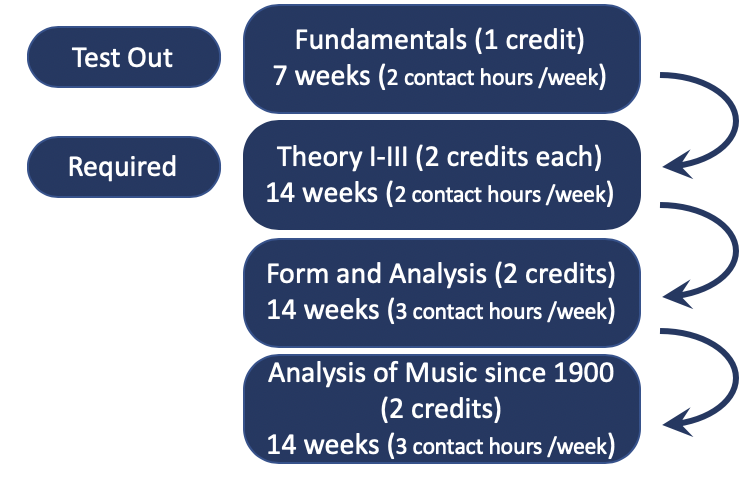

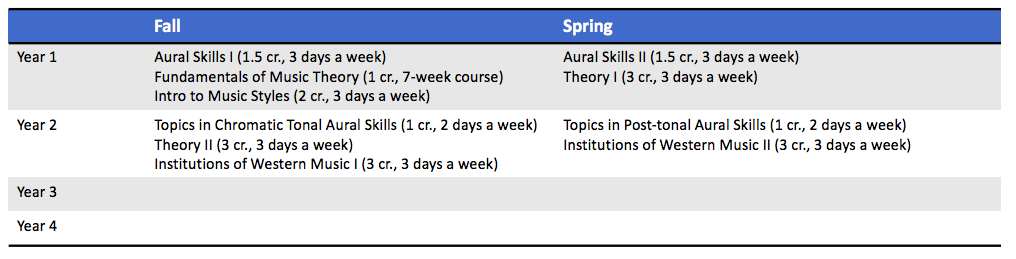

At the beginning of our discussion, we knew that we couldn't just keep adding to our curriculum––to add more experiences to the current Theory core would take a curriculum that is already packed and make it unwieldy. The current Theory core, as seen in Example 1, is a linear journey from fundamentals (course schedule here), through three semesters of theory centered on part-writing and analysis, followed by advanced analysis classes in tonal forms and post-tonal music.

While the Theory core has been successful for many years, some students (especially those entering college with limited music notation skills) struggle to complete the curriculum. These struggles are compounded by the limited face-to-face time in early Theory classes. Meeting two days a week does not provide enough guided practice for some of our students to form a solid foundation in Theory, and hence these students spend most of the core struggling to catch up. Further, the rigidity of the current curricular design creates difficulties for students who fall behind to complete coursework for graduation. To open the core to diverse students and pre-collegiate experiences, we decided to redesign the core from the ground up.

As we first started discussing diversifying the class content, we struggled with the problem of creating a curriculum that goes beyond token representation (Madrid 2017) and engages different music on its own terms. As Hess (2015) put it, we didn't want to be "musical tourists," cherry-picking vernacular and non-Western musical examples when they supported the learning objectives created for a Western canon. Such a model, which would increase the breadth of music experienced in the classroom, does not interrupt the overarching paradigm of the supremacy of the classical canon in the curriculum (Hein 2016). Instead we aspired to create a curriculum that centers on generalized musical skills our students need to be successful 21st-century musicians: thinking in music and thinking about music. Students then can apply these skills to a variety of musical traditions.

While as a collective body (10 full-time music theory faculty), some members of the Theory area at Ithaca College do research with diverse repertoires, reflecting the diversity in the field as a whole (Duinker & Léveillé Gauvin 2017), not everyone felt comfortable teaching the "thinking in music" skills with unfamiliar music. After all, our pedagogical training was rooted in the Western canon, and while resources are emerging that address diverse repertoires (see Open Music Theory; Holm-Hudson 2016; McCandless & McIntyre 2017), we wanted to create a curriculum that would cater to our collective strengths and individual interests while being flexible enough to accommodate faculty who would join us in the future.

Along with expanding the musical canon, we also discussed how we might increase student agency in our curricular design. When students take charge of their education, they tend to be more invested in the learning process (Cangialosi 2018), developing a deeper understanding of what they are doing and why they are doing it. Trusting students to make decisions about what experiences to include in their core theory experience necessarily shifts control of the specific content within a degree from faculty to students. This allows the curriculum to be geared towards individual student goals (Robin 2017), but we also wanted to be sure students graduated with the necessary skills to be successful as professional musicians and critical thinkers about music. As such we wanted to open the curriculum to allow for multiple paths while students met the same foundational learning outcomes.

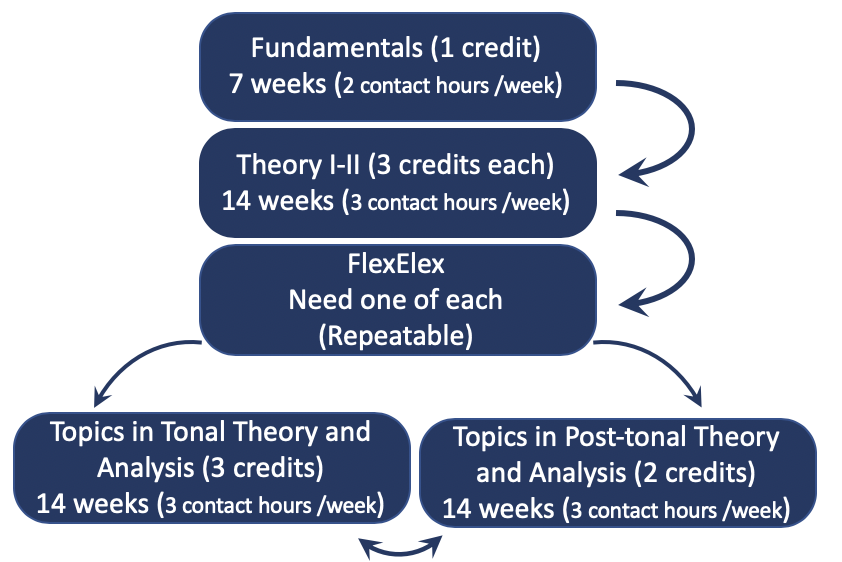

Out of this desire for student flexibility and diversity of repertoire we created a curriculum where students take a shared Theory I and II before electing upper-level classes in Tonal Theory and Analysis and in Post-tonal Theory and Analysis (Example 2). In this model, Theory I and II would be rooted in common practice, while the elective classes (affectionately called FlexElex) would be deep dives into particular repertoires. This model not only provides flexibility for students, who can take the upper-division FlexElex in any order, but also provides flexibility for faculty. As faculty interest and expertise changes, this model allows for flexible course offerings, building on our strength as a Theory area. After students finish the required topic courses (one of each), they may opt to take additional FlexElex, provided that the topics are different.

Our two-semester Theory sequence provides the foundation of broad analytical skills needed to excel in our upper-division classes. Because of the variety of advanced courses a student can choose for in-depth study, we needed to create a generalized set of skills upon which we could scaffold the upper-division study. Shifting the mindset of curricular design from covering topics in a textbook to teaching, modeling, and practicing skills that create significant learning experiences (Fink 2013) places student learning at the center of the curriculum. The following list summarizes the learning outcomes for the first year of theory study:

- Demonstrate fluency with the building blocks of tonal language (spelling chords, identifying keys, cadences, etc.).

- Recognize (aurally and score-based) and reproduce common harmonic paradigms (3-4 chords long).

- Explain and demonstrate voice-leading concepts such as resolution of tendency tones, consonance and dissonance treatment. Discern structural voices from more complex textures and coordinate them with a harmonic analysis.

- Analyze an unfamiliar piece of music (aurally and score-based) informed by an historical awareness of style, identifying small-scale and large-scale formal designs. Effectively communicate an analysis through prose and diagrams.

- Compose and improvise novel musical utterances in a style.

- Articulate bias in our analytical tools.

Most of these learning objectives are straightforward: refine notation and recognition skills from fundamentals, parse increasingly complex musical textures to analyze voice-leading and harmonies, and identify common formal designs. One of the most drastic changes in the new Theory I–II sequence, as compared to our current curriculum, is the move away from an emphasis on part-writing and figured-bass realization (Kulma and Naxer 2014) as a means to assess the student's understanding of harmonic syntax and voice-leading tendencies. Instead, we decided to focus on short, paradigmatic chord progressions that students would reproduce in 2 or 4 voices and use as a foundation for guided composition and improvisation assignments. We also wanted to provide students with authentic musical experiences from the very beginning, so the curriculum would need to include the analysis of complete pieces in order to ground students within a musical style (see Schubert 2011). Writing about music would also be introduced in these classes, in order to provide scaffolded writing assignments that would culminate in the upper-division classes.

Some of these skills are not particular to a single repertoire, so the decision to root these classes in common practice music was not taken lightly (although with the emphasis on the pitch and notation, it can be argued there is an inherent bias in the learning outcomes towards the Western canon). We seriously considered models like John Covach's integrative (Covach 2015) music curriculum or grounding the second class in Jazz, but ultimately opted for a more conservative approach. Since the institutional culture of Ithaca College follows a conservatory model, where most students perform music from the common practice repertoire, we felt that dedicated practice of applying these skills to this repertoire in the first year of theory study would provide a shared experience that would be applicable for the greatest number of students outside the classroom. The inherent danger in this model would be the implicit message that common practice music is valued more highly in our curriculum than other music. Our solution is to be transparent with our students regarding our explicit decision on the choice of repertoire in these classes. To meet our final learning objective, assignments will ask students to reflect on how traditional modes of engagement with particular repertoires shape analytical techniques, and how our analytical techniques highlight certain aspects of the music over others. This document provides more details on how we envision the course schedule for Theory I and II that will meet our learning objectives.

In the second year of music theory study, students choose from a set of courses in Topics in Tonal Theory and Analysis (loosely defined by music that is chromatic, yet tonally-based) and Topics in Post-tonal Theory and Analysis. While individual courses are still being designed for this curriculum, some possible electives for Topics in Tonal Theory and Analysis include: Formal and Cultural Analysis of Popular Music, Jazz Harmony and Analysis, Schenkerian and Structural Analysis, and The Tonal Language of Musical Theatre, among others. Whereas the aforementioned classes are weighted at three credit hours apiece, Topics in Post-tonal Theory and Analysis is only a two credit-hour course. This difference enables us to deliver the Theory curriculum in 12 credit hours, which includes the Fundamentals course. However, Topics in Post-tonal Theory and Analysis would still meet three hours a week in order to provide a space for extended guided listening sessions, since the premise underlying this course is to teach students to grapple with unfamiliar music. As such, "Post-tonal" is obviously a less-than-ideal name for courses which could include diverse topics like: Set theory, Serialism, and the Debates of 20th-century Music; Context and Analysis of Non-Western Musics; Analysis of Jazz in Post-Tonal Languages; and Music of Living Composers.

Uniting all the FlexElex are a shared set of student learning outcomes, and these are summarized below. These skills build directly on the skills taught in Theory I and II, challenging students to situate the musical text in an appropriate cultural context, analyze the musical text with the aim of creating an interpretation, evaluate musical interpretations, and communicate these interpretations through prose, diagrams, or other creative engagement with the text. These standard learning outcomes ensure consistency in the student's acquired skills in the curriculum, while maintaining flexibility for the student's choice in how to practice these skills and opening the curriculum to an in-depth study of a variety of music. Here is a sample syllabus created by my colleague, Peter Silberman, for Topics in Tonal Theory and Analysis, and here is my sample syllabus for Topics in Post-tonal Theory and Analysis.

- Analyze the formal design and hierarchical structures of an unfamiliar piece of music (aurally and score-based), choosing appropriate analytic approaches and techniques. Effectively communicate an analysis through prose and diagrams.

- Create and evaluate musical interpretations informed by:

- Stylistic norms and exceptions from the norms

- The function and meaning of musical elements such as pitch, harmony, centricity, melody, motives, rhythm and meter, time, texture, timbre, instrumentation, instrumental/vocal techniques, and recording effects

- Aspects of structural design

- Relationships between text and music

- Intersections with the culture in which it was created

- Creatively engage the repertoire studied, for example through composition, transcription, and/or improvisation.

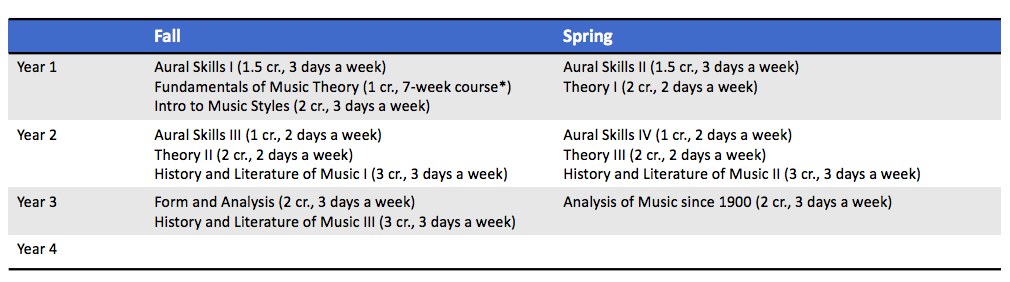

Along with these substantial changes to the Theory curriculum, the Music Theory, History, and Composition department made similar changes to the Aural Skills and Music History sequences. Although an in-depth discussion of these changes is outside the scope of this essay, a brief overview follows. The Aural Skills sequence begins with a two-semester common experience taken during the freshman year. These courses develop music reading and dictation skills through basic tonicization (V and III) and changing meter, and are followed by two classes where students practice advanced chromatic and post-tonal aural skills in a repertoire of their choice. Music History will not be taught chronologically with a focus on the Western canon (Haefeli 2015), but rather as a collection of case studies examining the interactions between music and "institutions" such as the academy, temple (places of worship), palace, stage, home, and market. This two-semester course is followed by an in-depth history elective. Example 3 illustrates the complete changes to the Theory, Aural Skills, and History sequence, which reflect our desire to decouple our curriculum from a single repertoire while freeing students to create their own pathways through the curriculum.

Example 3: Curricular Maps through BM Core Music Classes

a) Old curricular map for BM Degrees

*Students can test out of Fundamentals of Music Theory by earning a B or higher on the placement exam

You can see a description of these courses here.

b) New curricular map for BM Degrees

*Students can choose to take Topics in Music History (3) anytime after Institutions of Western Music II

*Students can choose to take Topics in Tonal Theory and Analysis (3) and Topics in Post-tonal Theory and Analysis (2) in any order, anytime after Theory II

While we initially set out to address the concerns of the students who walked out of class in Fall 2015, our success at creating a more inclusive Theory Core remains to be seen. We have indeed opened the curriculum for in-depth study of many types of music, but faculty still need to create courses within the framework of the topics courses. In our case, we already have faculty who specialize in topics such as Jazz, Pop, and Video Game music who are excited to create new courses, but we lack full-time faculty who specialize in the analysis of music from other parts of the world. I view this (perhaps overly optimistically) as an opportunity to petition for faculty lines to deliver needed curriculum and recruit faculty who are excited about teaching their research area to the undergraduate population. It is also possible for a student to elect course work that remains squarely within the Western canon. But the key word here is "elect." Students choose their course of study with the understanding that the thinking in music skills they develop are applicable to whatever music they encounter, professionally and personally.

The implementation of this curriculum is waiting for the completion of revisions across the various music degree programs at Ithaca College. The shift of credits in the Theory classes (from (1)-2-2-2, 2-2 to (1)-3-3, 3-2) changes individual degree schematics, which need to be accounted for in the new degree programs. Further, we are still working to create more agency and inclusion in other parts of the curriculum, like ensemble requirements and applied lessons. While the projected implementation date is still a few years off, I hope sharing our process of increasing representation and agency in our theory curriculum provides a model for other institutions undergoing similar discussions.

Bibliography

- Cangialosi, Karen. 2018. "Thoughts on Student Agency." Open Education (blog).

- Covach, John. 2015. "Rock Me, Maestro." The Chronicle of Higher Education.

- Duinker, Ben, and Hubert Léveillé Gauvin. 2017. "Changing Content in Flagship Music Theory Journals, 1979–2014." Music Theory Online 23 (4). https://doi.org/10.30535/mto.23.4.3

- Fink, L. Dee. 2013. Creating Significant Learning Experiences: An Integrated Approach to Designing College Courses, 2nd ed. John Wiley and Sons.

- Haefeli, Sara. 2015. "If History is Written by the Victors." The Avid Listener (blog).

- Hein, Ethan. 2016. "Cultural Hegemony in Music Education." The Ethan Hein Blog (blog).

- Hess, Juliet. 2015. "Decolonizing Music Education: Moving beyond Tokenism." International Journal of Music Education 33 (3): 336-47. https://doi.org/10.1177/0255761415581283

- Holm-Hudson, Kevin. 2016. Music Theory Remixed: a Blended Approach for the Practicing Musician. Oxford University Press.

- Kulma, David, and Meghan Naxer. 2014. "Beyond Part Writing: Modernizing the Curriculum." Engaging Students: Essays in Music Pedagogy 2. https://doi.org/10.18061/es.v2i0.7173

- Madrid, Alejandro L. 2017. "Diversity, Tokenism, Non-Canonical Musics, and the Crisis of the Humanities in U.S. Academia." Journal of Music History Pedagogy 7(2): 124–129.

- McCandless, Greg, and Daniel McIntyre. 2017. The Craft of Contemporary Commercial Music. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315680330

- Robin, William. 2017. "What Controversial Changes at Harvard Mean for Music in the University." National Sawdust Log. Accessed 19 May 2019.

- Schubert, Peter. 2011. "Global Perspective on Music Theory Pedagogy: Thinking in Music." Journal of Music Theory Pedagogy 25: 217–33.

- Shaffer, Kris, Bryn Hughes, and Brian Moseley. 2018. Open Music Theory. Hybrid Pedagogy Publishing.